You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven… You therefore must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect. (Matthew 5:43-45a,48)

In Matthew 5, Yeshua corrected a number of man-made doctrines and misunderstandings of Biblical principles. Although Leviticus 19:18 says “You shall love your neighbor as yourself”, there is no command in Scripture to “hate your enemy”. It’s easy to see where they would get such an idea, though. In Psalm 139, David wrote,

Do I not hate those who hate you, O LORD? And do I not loathe those who rise up against you? I hate them with complete hatred; I count them my enemies. (Psalm 139:21-22)

This sounds at first like David hated his enemies, but that’s not what he said. David hated “those who rise up against” God and also counted them as his own enemies. He didn’t say that he hated his own enemies, most especially those who merely hated God in their hearts–which is bad enough–but only those who took action on their hatred, who rose up against God in open rebellion, attempting to bring others into their error.

On the national level, the Tanakh (the Old Testament) records numerous instances of God commanding Israel to attack those who had made themselves enemies of God either by attacking God’s people directly or by attempting to lead them into sin through which they could be cursed and defeated.

This is exactly the strategy that Balaam taught Moab and Midian to use against Israel. By attacking Israel, those nations became God’s enemies. If they had attacked Israel only in self-defense, they would still be Israel’s enemies, but not necessarily God’s, and Israel would be in the wrong. But they didn’t attack Israel in self-defense. They didn’t even attack because they hated Israel, but because they hated God who had chosen Israel instead of them.

And the LORD spoke to Moses, saying, “Harass the Midianites and strike them down, for they have harassed you with their wiles, with which they beguiled you in the matter of Peor, and in the matter of Cozbi, the daughter of the chief of Midian, their sister, who was killed on the day of the plague on account of Peor.” (Numbers 25:16-18)

There is no instance of God commanding Israel to attack or hate anyone simply because they were rivals or enemies of Israel. Edom also hated Israel, but unlike Midian and the various Canaanite nations, they didn’t rise up against God. Despite centuries of conflict between the rival kingdoms, God commanded Israel to respect the boundaries of Edom until they were both conquered by Babylon.

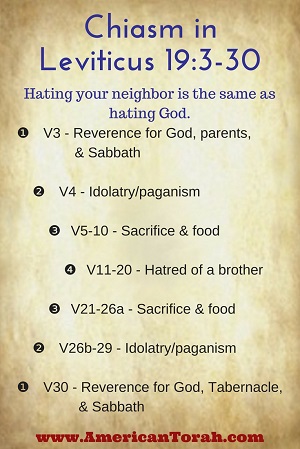

The same principle holds true for interpersonal relationships, especially between brothers among God’s people. In Matthew 5:43-48, Yeshua drew on the broader context of the original source of “love your neighbor as yourself”, Leviticus 19:1-30. This passage is structured as a chiasm (see here for more information on chiasms) in which commands to refrain from hateful behavior are sandwiched between instructions on sacrifice, refraining from idolatry, and reverencing parents, Tabernacle, and Sabbath.

- v3 – Reverence for parents & Sabbath

- v4 – Idolatry/paganism

- v5-10 – Sacrifice and food

- v11-20 – Fraud, oppression, hatred, mixtures, sexual abuse

- v21-26a – Sacrifice and food

- v5-10 – Sacrifice and food

- v26b-29 – Idolatry/paganism

- v4 – Idolatry/paganism

- v30 – Reverence for Tabernacle & Sabbath

This is very similar to another, much larger, chiastic structure in Exodus 25-40. In that instance, the idolatry of the golden calf, after which God commanded the faithful of Israel to kill their own brothers, is set between the stone tablets, Sabbath, and instructions for the Tabernacle. See more details on that chiasm here.

This is very similar to another, much larger, chiastic structure in Exodus 25-40. In that instance, the idolatry of the golden calf, after which God commanded the faithful of Israel to kill their own brothers, is set between the stone tablets, Sabbath, and instructions for the Tabernacle. See more details on that chiasm here.

God’s intent in this arrangement appears to be to equate unjust hatred for one’s brothers with idolatry, or hatred of God himself. To paraphrase God’s message…

Don’t steal from or lie to one another. Don’t oppress the powerless. Don’t hold hatred in your heart for your brother. Don’t speak ill of one another. Respect the boundaries I have created. Just like you, your brothers are created in my image and if you abuse them, it is like you are abusing me. My true worshiper not only offers sacrifices and reverences his parents, my sanctuary, and my Sabbath, but reverences his brothers, even those who have done him wrong.

Mercy is always God’s default position. He loves all mankind and doesn’t want even a single person to be lost. But for reasons of his own, he has created us able to reject him and each other. We are fully capable of theft, rape, and murder, and God doesn’t stop us from committing whatever wicked act comes into our hearts.

Just as he has empowered us to do evil, he has empowered and even commanded us to correct injustices. We are required to execute murderers and adulterers and to exact punishment and restitution where applicable.

The punishment of criminals and the destruction of entire nations who have sworn enmity against God is not counter to Yeshua’s instructions to love one another. It is impossible to love everyone equally as some are willing oppressors while others are innocently oppressed. To destroy the one is to love the other and God’s word is consistently in favor of the oppressed.*

Usually love means being kind and merciful, but sometimes love also requires violence.

*And by oppressed I don’t mean poor or uneducated. Those are conditions that might be the result of oppression, but they might as easily be the result of natural disasters or poor personal decisions. I mean people who are actively being oppressed by someone else and who are unable to defend themselves.

Update: Here’s a little more detail on that chiasm. The chiasm itself is actually one and one-half segments of a triple parallelism.

- V3 – Reverence (Mother, Father, Sabbath)

- V4 – Idolatry

- V5-10 – Sacrifices and food

- V11-12 – Fraud

- V13-15 – Oppression

- V16-18 – Hatred

- V19 – Mixtures

- V20 – Oppression/sexual immorality

- V21-26a – Sacrifices and food

- V5-10 – Sacrifices and food

- V26b-29 – Idolatry/paganism

- V4 – Idolatry

- V30 – Reverence (Sabbath, sanctuary)

- V31 – Idolatry/paganism

- V32 – Reverence (Elders)

- V33-36 – Oppression & Fraud

God commands quite a few things in Torah that don’t set lightly with most Westerners today. If two men are fighting and the wife of one of them rescues her husband by striking or seizing the other man’s testicles, should we cut off her hand? If a man is caught with another man’s wife, should we drag them both out to the city gates and stone them to death? Should we execute rebellious teenagers?

God commands quite a few things in Torah that don’t set lightly with most Westerners today. If two men are fighting and the wife of one of them rescues her husband by striking or seizing the other man’s testicles, should we cut off her hand? If a man is caught with another man’s wife, should we drag them both out to the city gates and stone them to death? Should we execute rebellious teenagers?

Leviticus (Vayikra in Hebrew) gets a bad rap. It’s usually dismissed by preachers and Sunday school teachers alike as tedious and irrelevant, full of blood and obsolete rules.

Leviticus (Vayikra in Hebrew) gets a bad rap. It’s usually dismissed by preachers and Sunday school teachers alike as tedious and irrelevant, full of blood and obsolete rules.