In this Common Sense Bible Study series, we’ve talked about many tools that can help you gain a better understanding of Scripture, about distractions that can lead you down unending, counterproductive rabbit trails, and about good personal study habits.

In this installment, I want to get into some more advanced topics. We’re going to step just a little bit beyond where basic common sense might normally take you…

Well, that’s odd…

Have you ever read something in the Bible that just left you scratching your head and wondering what possible reason God could have had for inserting that odd bit?

If you haven’t had that experience, then you need to close this email right now and go back to your Bible. You either haven’t read enough of it or you didn’t pay sufficient attention, because there is strange stuff everywhere, and it’s not there just for the entertainment value.

Writing materials in the centuries in which the Bible was compiled were very expensive. For most of history, scribes and printers used parchment and not paper for making Bibles, and they had to be copied by hand. There were no printing presses and no computers, not even a typewriter. It could take years of manual labor and the skin of hundreds of sheep to make a single copy of the Bible. Even if it were only the work of men and not God, they would have tried to keep the waste to an absolute minimum.

Surely God would put at least as much thought into the content of his communications as men would theirs!

I think we can be fairly certain that there is no wasted text in Scripture. Every word is important and is intended to convey meaning, and scribal errors have been repeatedly shown by competent scholars to be vanishingly rare. So if there seems to be something odd or pointless, the problem isn’t in the text. The problem is in our understanding of it.

Four Scriptural Oddities

There are four kinds of Scriptural oddities that I want to call your attention to:

- The dull

- The weird

- The repetitive

- The contradictory

The Dull

Patches of dullness are scattered through the Old Testament like sheep in a pasture. Genealogies, lists, censuses, textual schematics, detailed rituals… It’s difficult getting through some of those passages.

None-the-less, they are important. There was an immediate, practical purpose to everything recorded.

- Some genealogies were included to show lines of inheritance.

- Censuses show us the relative sizes of families and tribes, and help to explain why this tribe had this territory and that tribe had another.

- The Tabernacle was the focus of God’s presence among the people, and detailed instructions for its construction and use were absolutely necessary for the priests who would atone for sins and work in proximity to the unimaginable power of God. It was vital to the health of the nation and to the daily survival of the priests that they get it right.

But is that all there is to it, just public records and an instruction manual? Definitely not.

For example, Ezekiel 43:10 says, “As for you, son of man, describe to the house of Israel the temple, that they may be ashamed of their iniquities; and they shall measure the plan.” There is something about the design of the Temple that ought to make us ashamed of our sins. Clearly, the details weren’t written down just to make sure it was built correctly.

The original readers of Exodus and Ezekiel probably understood things about the symbolic meanings of numbers, shapes, and materials that we don’t. By examining how those things are used elsewhere in Scripture, we can get clues about what God meant by what he told Ezekiel. For example, various metals appear to be associated with spiritual ideas: gold with righteousness, silver with blood, and bronze with judgment.

For another example that might have been more obvious to ancient peoples, look at the many genealogies. In some cases, they are there to provide historical context or to prove lines of descent. In other cases, there is almost certainly something deeper intended. Keep in mind that names in the Bible have meanings and that something important about a person might be memorialized in the name–or names, since they sometimes changed–that has been passed down to us.

Think of a dull part of the Bible like a tapestry that seems plain and gray from a distance, but that becomes more detailed and complex the closer you examine it.

The Weird

There are sooo many strange things in the Bible, and not just because it’s the product of a very foreign culture. There are mysteries and things that are just plain beyond our comprehension.

How would you explain sales technique to an ant? It doesn’t use money or even barter. It doesn’t use speech, but has a language consisting of a small vocabulary of dance moves and pheromones.

That’s like God and us.

There is a great deal about himself and his thoughts that God hasn’t told us, either because it’s not our business or because we couldn’t understand it if he did. His language, his motivations, his plans are more complex than we can imagine.

Just as our communication methods are more varied and complex than that of ants, so are God’s more complex than ours. He can’t communicate with us directly in his own way. The closest we have ever come was at the foot of Sinai, and it nearly killed us.

Instead of spelling everything out in plain words, God couches much of his communication in stories, parables, and metaphors. A picture can communicate much more than a thousand words in a single glance. It can tell bare facts, but it can also reveal character and even relationships. Likewise, a well crafted story can tell more than just the story. An interlocking network of stories can describe plots within plots, sub-plots, a universe, perhaps even layers of universes.

A master story teller leaves indications–shadows–in his text of the stories behind the story, and God has left these clues everywhere in the Bible. Whenever you see something especially odd–an inexplicable action, a bizarre ritual, or a talking donkey–it’s a signal that you should stop and take a closer look.

Consider Balaam’s donkey. Although stories of miracles in the Bible are usually meant to be understood as literally true, some stories seem more out of place than others. Animals don’t talk, and there is no hint anywhere else in Scripture that we should expect them to as a miraculous manifestation of God’s power, so when the Bible tells of a talking animal, then the real story isn’t the talking animal, but something hidden beneath the bare text. When I was considering this portion of this article, I realized that there is only one other story in the Bible that involves a talking animal: the serpent in the Garden. The two stories must be connected.

Although the elements of the two stories are not in the same order, the parallels are astonishing: the crushed heel, the angel blocking the way, the questioning of God’s instructions, etc. Clearly the author of the Balaam story wanted his readers to see the connection, but since he didn’t explain why, he must have also wanted us to think through the connections for ourselves in order to learn something deeper.

Now, all sorts of truths and lessons could be derived from this particular connection, and I don’t intend to talk about them here. My point is that the connections exist. There are profound lessons to be derived from them if we are willing.

When something in the text stands out as odd or out of place, you can often gain a better understanding and even make some startling discoveries by looking for thematic connections with other passages.

The Repetitive

There are three different kinds of repetition in Scripture.

- A single phrase or theme might be repeated within a short span of text.

- A set of images, actions, or objects might reappear together in a distant part of Scripture.

- A word or phrase might be repeated with a twist in spelling or usage.

There is a lot of overlap in this section with the previous two. The first type of repetition often seems tedious and the second type signals thematic connections that highlight deeper truths behind seemingly unrelated passages.

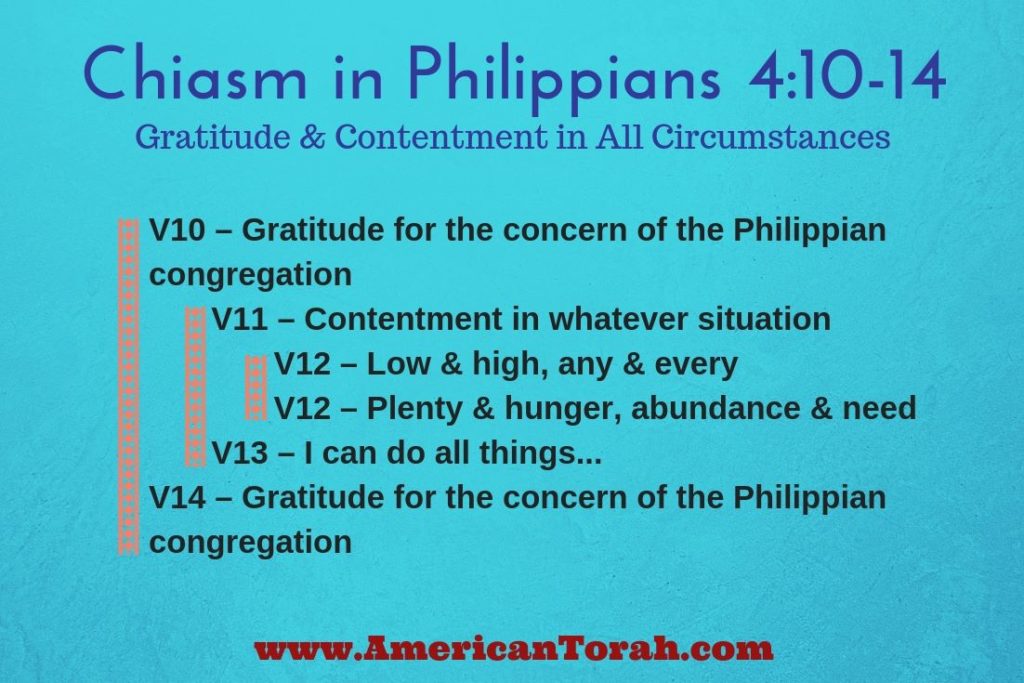

Parallelisms and Chiasms

Parallelisms and chiasms are some of the more interesting examples of repetition. They are literary structures meant to serve as mnemonic devices as well as to draw the readers attention to contrasts, central points, and connections within a block of text.

One of my favorite chiasms is in Genesis 27. In verses 18-19, Isaac asks Jacob, “Who are you?” and Jacob responds with “I am Esau, your firstborn.” In verses 31-32, Esau approaches Isaac and says “I am your firstborn, Esau,” and Isaac responds with “Who are you?” If you read this entire passage in a single sitting, when you get to verse 32, you might be left with a vague sense of deja vu, and you’re supposed to. If you work forward from verse 18 and backwards from verse 32, you’ll find a series of parallel events and statements in reverse order until you get to the center of the story in which Isaac sets aside his doubts and believes Jacob’s lie.

I posted a graphical representation of that chiasm here: A Chiasm Centered on the Deception of Isaac.

You can see my growing list of chiasms and parallelisms here: An Index of Biblical Chiasmi and Parallelisms.

Thematic Repetitions

Thematic repetitions, like the serpent and the donkey discussed above, are less structured than chiasms, but are no less significant. The Bible is packed full of them.

For example, the imprisonment and resurrection of Joseph is a foreshadowing of the death and resurrection of Yeshua.

In another example, the competing claims of Mephibosheth and Ziba on Saul’s inheritance during the reign of David (told throughout the book of 2 Samuel) are almost identical to the claims of the two women on the same baby during the reign of Solomon (told in 1 Kings 3). The former story was left with an unsatisfying resolution, but in the second story, the child was restored to his real mother because of Solomon’s shocking proposal to cut the baby in two. The writer’s intent was probably to show how the son’s wisdom had eclipsed even that of David, his illustrious father.

There are many, many more examples.

Anaphora

Anaphora is the repeated use of the same or very similar words in successive phrases or sentences as a form of emphasis or parallelism.

This third category of repetition might be the easiest to miss and sometimes can only be clearly seen in the Hebrew. In Biblical anaphora, a word or phrase is repeated in order to emphasize different meanings. The repeated text might be changed slightly to illustrate a difference in perspective or intent, as in the commissioning of Joshua in Deuteronomy 31 (See more detail on that here: Shadows of Jesus in Joshua) and Yeshua telling Peter to feed his sheep in John 21, but it could also use the exact same words each time, relying on oral tradition or greater context to draw out the real meaning, or even on puns that are frequently lost in English translations.

Remember that God doesn’t waste words. He doesn’t repeat himself without reason, so when you see repetition, ask why, and look for differences and similarities.

The Contradictory

We’ve all heard about the many so-called contradictions in the Bible, and since you’re still reading this, you probably already figured out that most of them aren’t contradictions at all. They’re obviously taken out of context and deliberately misinterpreted by dishonest people with an anti-Christian agenda.

On the other hand, we have to be honest with ourselves about some troublesome passages too. There really are some sticky conundrums in the canon. I’m willing to concede that there might be some scribal errors in some of the historical books, but there are some other apparent contradictions that can’t be dismissed so easily.

Take this one, for instance:

Deuteronomy 15:4 says, “There will be no poor among you.” Yet just a little further down the page, verse 11 says, “For there will never cease to be poor in the land.” Which is it? Will there never be poor or will there always be poor?

For another example, one of God’s many titles is YHWH Tsevaot, which means, God of Armies. Yet Paul tells us in 1 Corinthians 14:33 that he is a God of peace. Which is it? Is he a God of Armies or a God of Peace?

Whenever you encounter apparent contradictions like these, the first thing you can be sure of is that there is no contradiction. The conflict can be resolved by adjusting your perspective. One or more statements could be metaphor or intended to be limited in scope. In the example from Deuteronomy 15 cited above, one statement could be meant as a goal, while the second could be an observation about how life is actually going to play out. No plan of battle ever survives first contact with the enemy, as they say.

There could be any number of explanations for apparent contradictions, but you’ll have to dig for them. You’ll have to study and think to find a resolution, and that’s a good thing! The Bible isn’t a children’s story book, and it wasn’t designed for casual reading.

God Loves Patterns

His creation is a complex weave of interconnected, synergistic parts and modular sets of instructions that serve multiple, simultaneous purposes in widely varying circumstances. His word written on paper is built on the same principles as his word written in the stars and in DNA.

When you step back from the Scriptures and examine them more broadly, you will see things that you can’t see from close up. When you examine them in minute detail, you will see things you can’t see from a distance. And when you turn them just so to look from another angle, the light is refracted as in a diamond into yet more beautiful patterns.

You will never know everything there is to know about God and his plan. You can study the Bible for a dozen lifetimes and still find new layers, new truths, new wonders that testify to God’s infinite wisdom and creativity.

Enjoy the treasure hunt. It’s part of what we were built for.